In Mali the Grand Mosque of Djenne is given a new coat of mud plaster each spring to replace the coating washed away by the rainy season (click thumbnail for large image).

Photo: Christian Jaspars/Panos

Earth is one of man's oldest building materials and most ancient civilizations used it in some form. It was easily available, cheap, strong and required only simple technology. In Egypt the grain stores of Ramasseum built in adobe in 1300BC still exist; the Great Wall of China has sections built in rammed earth over 2000 years ago. Iran, India, Nepal, Yemen all have examples of ancient cities and large buildings built in various forms of earthen construction.

It is significant that the oldest surviving examples of this building form are in the most arid areas of the world. The strength of unstabilised earth walls comes from the bonding effect of dried clay. If this becomes wet the strength is lost and indeed the wall will erode or even fail completely. Different countries have different approaches to this problem.

In Mali the Grand Mosque of Djenne is given a new coat of mud plaster each spring to replace the coating washed away by the rainy season (click thumbnail for large image).

Photo: Christian Jaspars/Panos

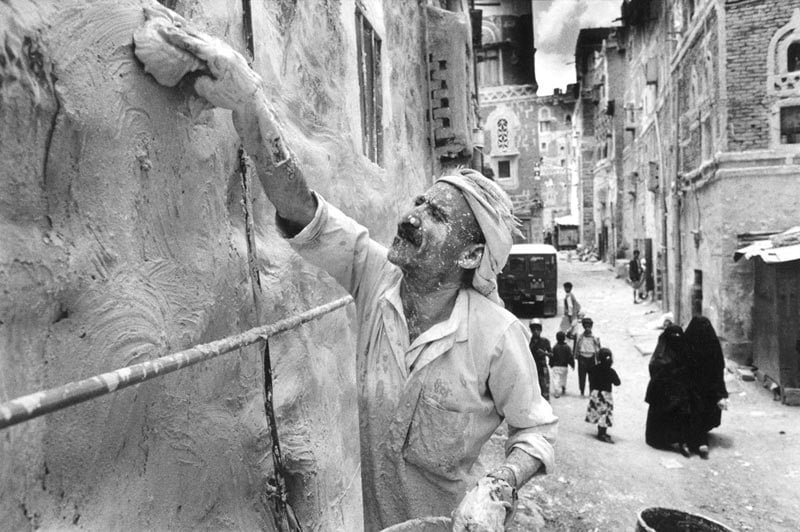

In the Yemen specialist workers burn limestone to make hydraulic lime with which they plaster their earth buildings

Photo: Tim Dirven/Panos

In England there is ample evidence of earth’s use as a building material, as around 60% of scheduled “ancient monuments and archaeological sites” are constructed of earth or have earthworks associated. But it became regarded as a material of limited durability and thus inferior to more permanent materials, such as stone or fired clay bricks. Consequently, within the last few centuries, it has most commonly been used for workers cottages, barns and perimeter walls where cost was more important than longevity. This is evident from the fact that fewer than 2% of the 450,000 listed buildings in England are made of earth.

The modern version of earth building, which is stabilised to solve the longstanding problem of solubility, has developed through an interesting set of international connections. An English trained Architect and Engineer, George Middleton, worked at the Experimental Building Station in Sydney in the late 1940’s. Looking for methods of building low-cost housing, he experimented with stabilising earth and produced a publication from the Station: “Bulletin 5, Earth Wall Construction”, which eventually became a standard reference for earth building in Australia. In 1953 he published a book: “Build Your House of Earth; A Manual of Earth Wall Construction”, which has been reprinted several times. Middleton advised the Israelis on low-cost housing and their developments were published in "Soil Construction - Its Principles and Application for Housing" in 1957 by S. Cytryn. This publication, which introduced the term Stabilised Rammed Earth, came to the notice of the architect Tom Roberts and artist Giles Hohnen in 1975 in Western Australia. Their interest in earth-wall building started with the search for an aesthetic and cost effective wall material for a new Winery at Margaret River. Western Australia at the time was a “brick and tile” state, with the only other option, timber frame, viewed as a “low rent” building material, actively discouraged by local councils. This, combined with the 1973 OPEC oil price hikes (prices quadrupling between 1973 and 1974 and rose a further 150% in 1979 in the wake of the Iranian Revolution) created an inflationary period that the brick industry seemed to be cheerfully exploiting. Apart from jacking prices, they were able to dump failed experiments in brick and tile fashions on the country builders and Margaret River was facing a creeping rash of what they called “ tropical disease” houses with speckled mixes of brown, cream, white, pink and green walls and roofs.

Based on Cytryn’s advice, these men took the critical decision to use local lateritic gravel and stabilise it with a low percentage of (approx 2-3% initially) cement rather than use earth with 40% clay as had been done previously in Australia. They built a shed in Stabilised Rammed Earth at Cape Mentelle in 1976 to demonstrate to the Council the durability and strength of the material, which still stands today in pristine condition unaffected by the weather. The following year the council approved the construction of the first stage of the winery and within 10 years approximately 20% of new houses in the shire were of SRE. This was the start of a SRE building boom in Margaret River, Western Australia, where within a few years, 20% of new houses were being built in this new material.

At about the same time, David Eastern in the USA and Patrice Doat and Hugo Houben in France were rediscovering earth building. They initiated renewed interest in their countries and have built many buildings since, extending their knowledge and publishing excellent books on this subject.

Despite the excellent publications and numerous example buildings by Easton in the USA and CRATerre in France, earth building has grown slowly in America and Europe. There are now about a dozen SRE builders in the southern states of the USA, whereas Europe does not appear to have any dedicated SRE builders.

However, in Australia, the popularity of SRE houses in WA created a demand for builders able to offer this new, attractive building form. Numerous contractors set up in business to offer this new technique, but not all had the required skills. Giles Hohnen thought that some cooperation amongst them would be beneficial, so in the mid 1980’s he set up asEg.

asEg - The Affiliated Stabilised Earth Group

For an initial joining fee and a continuing small percentage of sales, this industry group offered initial training, technical advice, cooperation on large jobs and the establishment of a database of all members work. asEg members are now in all Australian states and have built more than two thousand buildings of many different types and applications. A standardised formwork system (Stabilform) which can withstand the stresses of ramming and yet is fast and easy to erect, has been developed specifically for building SRE. A water-repellent admix (Plasticure) has been developed which is now used by all members. This repels water from the finished walls whilst also improving their strength. This allows the specified strengths to be achieved with lower percentages of stabiliser. The improving technical ability and assurance of quality offered by members has attracted leading architects to use this new material in modern architecture. In 1997, NATSPEC, the Australian national building specification system released its first Monolithic Stabilised Earth Walling Specification. This was largely based on the work carried out by asEg. Since then many governmental and semi-governmental bodies have become interested in this building medium and significant numbers of public buildings have been completed.

Earth Structures has been a member of asEg since 1992 and has made its own contributions to the development of this new technology. Recent innovations include:

Preferential use of cement that includes 30 to 35% GGBS, which is a cementatious industrial waste product from the steel industry that often otherwise has to go to land fill. This effectively reduces the cement used by the same percentage.

Development of SRE walls which incorporate insulation. These walls can meet UK Building Regulations for heat transfer and yet maintain a high thermal mass within the building, which aids thermal levelling.

Developed the technology for building SRE walls from Recycled Demolition Waste. Effectively this provides the means of recycling old buildings on brownfield sites to provide the materials for new recycled buildings.

Developed techniques for building and installing prefabricated panels of SRE. This appears to have exciting possibilities for production efficiencies and providing solutions in tight or difficult to reach sites.

Visit our Image Gallery to see photographs of some of the buildings incorporating these developments.

England has an ancient heritage of earth buildings and it has well funded bodies whose main focus is the preservation of this heritage. ICOMOS UK (International Council of Monuments and Sites) and English Heritage produced a study of earth building traditions in Great Britain and Ireland titled “Terra Britannica” in 2000. They were also the main supporters of “Terra 2000”, an international conference focussed mainly on the preservation and repair of old earth structures.

In an article entitled: “Traditional crafts updated: thatching and cob”, published in Structural Survey, Vol 13, No 4, 1995, Tony Ley writes:

"It is not uncommon for thatch roofs to have been removed and replaced by slate, tile or wrinkly tin. The new roof fails to provide the same overhang as the thatch. Consequently more rain contacts the surface of the wall, eventually causing local saturation, resulting in cracking or partial collapse, especially in the areas of roof or floor beams. These conditions can be aggravated where tiles or slates are missing. Once cob reaches saturation level it moves through the plastic stage quickly and slumps dramatically, resulting in extensive collapse."

Photo: An old earth wall in Great Easton, Leics. A leaking roof has allowed erosion so the wall is becoming unstable.

English Heritage had a problem as it was aware that the stock of old earth dwellings and barns was rapidly dwindling as lack of maintenance and inappropriate treatments caused failure. Modern building had superseded this labour intensive old method and the skills of building and maintaining earth walls were rapidly being lost. Financial support encouraged academics and individual enthusiasts to study the old ways.

Specialist groups of enthusiasts and conservators have set up across Britain:

-Centre for Earthen Architecture, Plymouth University - started out with research into how the moisture content of mud walls affects their strength. This research was needed due to the high demand for advice on the large number of earth buildings with damp-related faults in Devon and surrounding areas.

-DEBA: Devon Earth Builders Association - Larry Keefe

-EARTHA: East Anglia Regional Telluric Houses Association - Dirk Bouwens

-EMESS: East Midlands Earth Structures Society - David Glew

-HADES: Harborough and Daventry Earth Structures Group

These groups have conducted surveys and try to promote awareness of historic earth buildings in their respective areas, e.g. attending country fairs, open days on historic buildings and reconstructions.

This interest in traditional practices and conservation of historic earth buildings has resulted in a number of specialist practitioners developing old skills. The Retro movement has been inspired by people like Alfred Howard in Devon, who used to build traditional mud cottages in 1930’s then reintroduced it to the next generation in 1984, e.g. Kevin McCabe (got involved through EH) - built a mud bus shelter. This was credited with being the first earth building in Devon for over 50 years.

“Proper conservation can only occur by raising the status of the material by promoting new build” - Dirk Bouwens.

The enthusiasm of the researchers and practitioners for the ‘old ways’ has now grown towards actually promoting these as modern building methods. It is widely acknowledged that high-strength, modern cement materials are highly unsuitable for most historic building applications as they are incompatible with the level of movement and moisture penetration that has to be considered by conservators. Unfortunately this has led to an irrational & aggressive campaign aimed towards eliminating the use of cement in modern masonry walls. However, this approach is proving counter-productive; without a sustainable alternative to the cost-effectiveness of cement it is unrealistic to expect attitudes in the construction industry to change. The principle of lowering standards in construction and promoting historic techniques as the future of sustainable building is misguided. Modern sustainable building materials must be cost-effective, quick to build, and capable of competing with the more conventional alternatives such as bricks and concrete block.

Old earth walls incorporated into modernised old buildings. Although fitted with extended eaves, surface erosion is occurring.

"We note also that in the United Kingdom and France that earth walling is limited to the smaller domestic and farm buildings. In the old villages the parish church and the manor house, and any buildings having more considerable architectural pretensions, were invariably built of brick or stone. Thus we may take as a tacit admission that unstabilised earth walling did not possess sufficient permanence to justify the expenditure of a large amount of effort and elaboration in fittings and decorative work." (Fitzmaurice, 1958, p5)

The Earth Centre at Doncaster, now sadly closed, was an early setback for the promoters of the old ways of earth building in England. Forecast as a great public attraction showcasing sustainable ideas, the designers were considering using Australian earth builders to construct the walls for some of the main buildings. But this approach was criticised because the walls would contain a small percentage of cement. Unstabilised rammed earth was aggressively promoted but efforts were severely impeded by uncertainties over material suitability combined with very little evidence to show this method was actually feasible for a modern public building. Ultimately, this idealistic campaign was counterproductive; it resulted in the contractors using standard concrete and abandoning earth construction altogether.

This type of bickering between different factions of the environmental building movement does not help either cause and must contribute to the slow progress of all forms of earth building in the UK. Only about a dozen earth buildings have been built in England in the last decade, half stabilised and half unstabilised. Until the supporters of the different codes of earth building can accept that each has a place in the market and a type of client who will value the qualities that their code offers, then the more important job of building sustainable buildings will be greatly hampered.

The Centre for Alternative Technology have built an attractive unstabilised rammed earth wall in their new bookshop, but made sure that it is not exposed to any weather as it is an internal wall in a timber building. They have also clad it in Perspex to ensure the public do not touch it.

The Eden Project has an unstabilised rammed earth wall on one side of the visitors centre, built by Rowland Keable. This ran well behind schedule during construction and the main contractors said they would not wish to repeat the experience. Despite being protected by an extended roof the wall is suffering severe erosion from the weather.

Dirk Bouwens, Secretary of the East Anglian Earth buildings Group in the article ‘Earth Buildings and Their Repair’ for the Building Conservation Directory 1997, stated: "The strength of (unstabilised) earth walls is proportional to their moisture content. At a moisture content of 13% of its dry weight the strength of the material falls to a point where it can no longer resist the pressure exerted by an average wall (c.0.1N/mm2). At this level the wall may collapse."

Ancient Practices still thrive today in third world countries where materials such as cement are prohibitively expensive. The traditional technique of hand rammed earth was promoted in Zimbabwe by Julian Keable and his son Rowland. They empowered the poor to build their own mud buildings and shelters. Now, Rowland is also working in the UK and has built nearly half a dozen traditional earth structures to showcase the way that our ancestors used to build with earth in this country. As with all re-enactments of tradition that are faithful to their origins, these traditional earth walls are expected to slowly wash away, crack and crumble just as they would have done hundreds of years ago (e.g. Eden Project). This gives a very ‘natural’, rugged appearance complete with bulges, distorted openings and authentic leanings walls - these traditional, natural earth walls really look as though they were built 200 years ago!

The demand for this tiny cottage industry is slowly growing, particularly in rural areas where the ancient tradition originally flourished. In 2004 the DTI even funded a research project, conducted by Dr Peter Walker (University of Bath) & Rowland Keable, to investigate the further potential of this ancient technique for use in authentic reproduction historic housing. The project was called “Developing Rammed Earth Walling for UK Housing”. The project included a case study building project called the Bird in Bush Centre, which used the unique skills of Rowland Keable to produce authentic ‘natural’ earth walls.

"In the case of unstabilised rammed earth, it is arguable that the key issue is not the amount of water that penetrates a wall but the fact that the presence of moisture has the effect of lowering its compressive strength and causing erosion and loss of structural integrity. It is perhaps obvious that in developed countries such as Great Britain the level of performance that is expected from modern building materials cannot typically be delivered by unstabilised earth materials. For developing countries such as Algeria, the use of cement is often prohibitively expensive due to economic and political constraints and the warm, dry climatic conditions are well suited to the use of low-cost materials such as unstabilised earth. Conversely, in Great Britain Approved Document 7 from the Building Regulations (2000) for England & Wales requires that construction materials should, for example, conform to a recognised British Standard or bear CE certification. Currently there are no recognised standards for stabilised rammed earth (SRE) construction in Great Britain. However, a precedent for its acceptance has been granted for an SRE building project by Chesterfield Borough Council under section F (experimental investigations) of Approved Document 7 based on the work conducted by the authors. Under these regulations, the use of SRE walls for external masonry wall elements must additionally satisfy Approved Document C - Section 4 and so must:

-not be damaged by rain or snow

-resist the passage of rain (or snow) to the inside of the building

-not transmit moisture due to rain (or snow) to another part of the building that might be damaged"

Cited in: Hall M & Djerbib Y, 2005, "Moisture Ingress in Rammed Earth: Part 3 - Sorptivity, Surface Receptiveness and Surface Inflow Velocity". Construction and Building Materials.

Typical old village walls in the Leicestershire/Northamptonshire earth building belt.

Close up of insect infestation common in these walls.